José María Mazón Sainz

José María Mazón Sainz | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | José María Mazón Sainz 1901 Haro, Spain |

| Died | 1981 (aged 80-81) Madrid, Spain |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | entrepreneur |

| Known for | politician |

| Political party | Carlism, FET |

José María Mazón Sainz (1901–1981) was a Spanish lawyer and a Traditionalist politician. In the early 1930s he was active within Carlism and rose to party leader in the province of Logroño. Engaged in the coup of July 1936, during the Spanish Civil War he favored unification into the state party. His political career climaxed at the turn of the decades; in 1937–1938 he held a seat in the first Falange Española Tradicionalista executive Junta Política and in 1937–1942 during two first terms he was member of another top party structure, Consejo Nacional. In return, he was expulsed from Comunión Tradicionalista. In the early 1940s he withdrew from politics and led a Madrid law firm.

Family and youth

[edit]

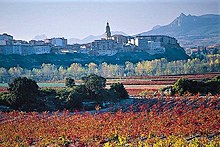

The family of Mazón was first noted in Cantabria; in the modern era it became fairly popular in the then Castilian provinces of Santander and Burgos.[1] The branch which José María descended from was related to the municipality of Ramales, located in the mountainous Cantabrian hinterground area known as Sierra de Rozas. His first identified ancestor was Juan Mazón, though it is not known what he was doing for a living.[2] The son of Juan and the father of José María, Eugenio Mazón Gómez, became a pharmacist.[3] At unspecified time though probably in the 1890s he married Clotilde Sainz.[4] Prior to 1897 (exact year unknown) Mazón Gómez assumed the pharmacy in Haro, at that time a mid-size Riojan town in the province of Logroño.[5]

The couple had 7 children, born between 1894 and 1919; the first two died in their very early infancy[6] and José María was the oldest son and the second oldest sibling who reached mature age,[7] followed by two other sisters and one brother.[8] He spent his early childhood in Haro, though nothing is known about his early schooling. To pursue secondary education in his early teens he moved to the Alavese capital Vitoria, where he started frequenting the local Instituto; in 1913 he was noted for excellent marks.[9] In the second half of the 1910s[10] Mazón commenced law studies at an unspecified university. He graduated in the early 1920s, and in 1922 he was admitted to Cuerpo General de Administración de la Hacienda Pública, a corporative organisation for a branch of civil servants.[11] He returned to Haro and started practicing as a lawyer; in the second half of the 1920s Mazón was on his own representing parties in court.[12]

Some time prior to 1929 Mazón married Consuelo Verdejo from Haro; nothing is known about her or her family.[13] The couple had 3 children. Verdejo was last noted as Mazón’s wife in 1955.[14] There is no information on her later fate; however, in 1956[15] Mazón was reported as married to his relative, Emilia Sainz Palomera (died 1989).[16] She originated from Carranza,[17] from a pharmacy-related family,[18] and widowed following an earlier marriage.[19] They had no children.[20] Among the children from the first Mazón’s marriage Eugenio during late Francoism became director general of Correos y Telecomunicaciones[21] and of Obra de 18 Julio;[22] he was moderately engaged in Traditionalism and served in the Cortes in 1971–1976.[23] Among Mazón’s grandchildren from Mazón Lloret, Saavedra Mazón and Martínez del Campo Mazón families the best known is Vega Mazón Lloret; she represents the third generation running the family law firm in Madrid.[24] Mazón’s younger brother Claudio was also moderately involved in Carlist politics.[25]

Restless Riojan Carlist

[edit]

Eugenio Mazón was a vehement Carlist; in 1908 he served as secretario general of the movement’s Junta Local in Haro.[26] José María Mazón and his siblings[27] inherited political outlook from their father and were brought up in zealous Carlist ambience; when filling the routine depuration questionnaire in 1940 he noted against the point about membership in political organizations: “I have been a Carlist since February 26, 1901, the day I was born”.[28] However, first information on his public activity is related to primoriverrista structures and generic Catholic circles; in 1923 he was noted as a member of Somatén[29] and in the mid-1920s as a speaker at Cultural Harense, a local Christian ateneo.[30] At the turn of the decades he was already a recognizable local right-wing figure. During local elections of April 1931 he was voted into the Haro ayuntamiento; in the left-wing dominated body he assumed leadership of the opposition “minoría Católico-Monárquica”.[31]

In Haro the Republic years of 1931–1936 were marked by high level of tension in the town hall; Mazón was among the protagonists of the conflict. Having lost the elections for the post of the mayor he protested composition of the local municipal executive, as alcalde and tenientes de alcalde were selected from the victorious Radical-socialist coalition with not a single post of power shared with the opposition minority.[32] As member of comision de instrucción he tried to oppose secular education,[33] protested changes of street names in line with the new Republican fashion, and worked to retain traditional flavor of local popular feasts.[34] Ignored or outvoted, eventually right-wing councillors ceased to attend the town hall meetings.[35] At the same time Mazón mobilized Carlist support in Haro[36] and elsewhere,[37] while his wife animated the local Margaritas organisation.[38]

During the anarchist rising of January 1933 Mazón and right-wing concejales re-appeared in the town hall, declaring the need to ensure law and order; they were ridiculed by the mayor.[39] In return, in 1934 Mazón accused him of promoting unyielding subversive education[40] and fomenting revolution.[41] He remained busy speaking at Carlist rallies in La Rioja[42] and in 1934 he was already acting as the Carlist jefe provincial in Logroño.[43] The year of 1935 produced further propaganda activity of Mazón[44] and his wife.[45] In November he again withdrew from the ayuntamiento claiming that new elections were long overdue[46] and focused on buildup of the local Carlist paramilitary organisation, requeté.[47] He worked for the Carlist cause during the February 1936 general elections; Comunión Tradicionalista candidates gathered 945 votes in Haro, but Frente Popular candidates emerged victorious.[48] Following assassination of a Carlist militant in Haro, in April he formatted the funeral as a Traditionalist demonstration.[49]

Unification protagonist

[edit]

According to his own declaration Mazón collaborated with the military when preparing the July 1936 coup, but no details are known.[50] The province was easily seized by the rebels; on July 29, 1936 Mazón was nominated to comisión gestora, which acted as the new Haro ayuntamiento.[51] There is scarcely any information available on his activities during first months of the war;[52] it is known that his role of the party jefe provincial was converted into the provincial Carlist comisario de guerra.[53] He was first noted as taking part in nationwide executive structures on March 22, 1937, when all provincial comisarios de guerra gathered in Burgos to discuss the threat of would-be amalgamation into a state party.[54] Within the strongly divided body Mazón was among the Rodezno-led faction which supported compliance with the military pressure; they prevailed and he formed part of a 5-member delegation tasked with communicating the news to Franco.[55] Generalissimo saw them on March 27, appeared delighted and asked them to act “in the spirit of unity”.[56]

On March 29 Mazón and other unification-minded Carlists travelled to Lisbon to agree the way forward with the exiled party leader, Manuel Fal Conde. The latter was furious; he accused them of undermining the party and refused to contact them any more.[57] On April 4 Mazón took part in the Pamplona sitting of the Navarrese Junta Central, the foci of unification faction; the present devised a last-minute plan of a directorio of the future state party.[58] Fal dubbed this stand as a coup against the CT authority, but on exile in Portugal he remained powerless.[59] On April 12 Conde Rodezno as leader of the unification-minded Carlists visited Franco to discuss details.[60] The Generalissimo proposed a list of Carlists to enter the planned executive of the new state party, Junta Política. Rodezno responded that it contained too many Navarrese and suggested that a Navarro Marcelino Ulibarri be replaced with Mazón.[61]

On April 19 the Franco headquarters issued the Unification Decree, which declared merger of Falangists and Carlists into the new state party, Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las JONS. Mazón acknowledged it the same day with Sesión Extraordinaria de la Comunión Tradicionalista de La Rioja in Miranda de Ebro; the gathering declared “la felicitación más entusiasta” and “más ferviente e incondicional adhesión”, ending with "¡A sus órdenes, mi general!”[62] On April 23 the military administration issued another decree; it named 10 individuals as appointees to the FET Junta Política. Mazón was listed at position #8, as the last Carlist after Rodezno, Florida and Arellano.[63] Thanks to his loyalty to Rodezno within the period of one month Mazón converted from one of 20-odd provincial Carlist comisarios de guerra, barely known beyond his native Logroño province, into one of 10 leaders of the monopolist emergent state party,[64] who might have appeared as the most powerful politicians in the Nationalist Spain.[65]

Francoist hierarch

[edit]

In June 1937 Mazón suffered major though not life-threatening injuries during a car crash;[66] he spent two months under intense treatment and returned home in August.[67] In late summer of 1937 he was back to political duties, still operating within the personal circle of Conde Rodezno. All Carlist members of Junta Política attempted to remain on correct terms with the regent-claimant Don Javier and declared that within Falange Española Tradicionalista they worked to ensure Traditionalist domination in the state party structures. However, among the Javieristas they were increasingly viewed as half-traitors who pushed towards unification and undermined the Carlist political identity.[68] In October 1937 Franco made a further step on the path towards institutionalization and appointed members of a new Falangist command structure, Consejo Nacional; among its 50 members there were 12 Carlists, and Mazón was on the list.[69] In unclear circumstances his Junta Politica term expired by March 1938.[70]

In 1938 Mazón remained engaged in FET organization work[71] and mass rallies nationwide;[72] his wife was active in the Frentes y Hospitales section.[73] First months following unification were marked by fierce competition between the Carlists and the Falangists; the latter were clearly gaining the upper hand, and soon Carlist heavyweights within FET were getting bombarded with protests from the rank-and-file, who complained about Traditionalist marginalisation in the state party. However, there is nothing known about Mazón objecting to Carlist disempowerment.[74] Quite the opposite; Mazón demonstrated full alignment with the Falangist domination and unlike most other unificated Carlists he sported an all-black uniform “de los falangistas más radicales”.[75] Eventually Fal Conde and Don Javier concluded that Mazón and other party members who engaged in buildup of the Francoist regime went off limits; in July 1938 they were expulsed from Comunión Tradicionalista.[76]

Mazón, who kept considering himself a Carlist,[77] did not pay much attention to expulsion. In March 1939[78] he accepted Franco’s nomination to Tribunal Nacional de Responsabilidades Políticas, a judiciary body set up to deal with top-placed Republicans who fell into the Nationalists’ hands.[79] In September 1939 his term in Consejo Nacional of FET expired; Mazón was nominated to the II Consejo, this time as one of 13 Carlists among 96 members of the mammoth institution.[80] In 1940 he was still taking part in various pompous Francoist ceremonies,[81] yet at the same time he started to prepare his exit from politics.[82] In 1941 he was dismissed from Tribunal Nacional de Responsabilidades Políticas.[83] In the autumn of 1942, when the term of II Consejo Nacional came to the end, he was consulted by the Franco’s entourage whether he would like to go on; however, Mazón declared he wanted to leave politics.[84] As a result, in November 1942 he was not nominated to the III Consejo Nacional.[85]

Businessman and retiree

[edit]

Starting 1943 Mazón was a private person with no official duties. Already 3 years earlier he ensured his admittance to Colegio de Abogados de Madrid, with references to be provided by Conde Rodezno.[86] In the 1940s he set up his own law firm, later to be known as Mazón Abogados;[87] his clients were major institutional customers, including Banco de España. At one point Mazón became asesor jurídico of the central bank[88] and he kept performing this role at least until the early 1960s.[89] At that time he was already joined by his son Eugenio, who was gradually taking over management of Mazón Abogados and juridical services of Banco de España;[90] however, José Maria was listed as abogado en ejercicio until the late 1960s.[91]

Since the mid-1940s Mazón stayed clear of politics. He did not join any Carlist initiatives, be it those originating among the Javieristas[92] or those related to Rodezno, who was increasingly leaning towards the dynastic leadership of Don Juan. He was admitted at a personal audience by Franco in 1954,[93] 1956[94] and 1961.[95] Since the mid-1950s he was anxious to shake off last vestiges of fascism and enlarged the Traditionalist contingent in the Cortes. However, in the early 1960s Mazón was consulted by the FET Consejo Nacional during works on the new Fuero del Trabajo.[96]

According to some sources during mid-Francoism the likes of Mazón were entirely ignored by mainstream Carlists as traitors not to be dealt with; when already as a retiree he appeared during Día de Santiago in Haro, he was pushed out by militant young Carlists; also Eugenio was ostracized when taking part in the Montejurra ascents.[97] However, when in 1958 Eugenio was getting married, the ceremony was attended – apart from carlo-franquistas like Esteban Bilbao – also by the Comunión leader José Maria Valiente and by José Luis Zamanillo. Moreover, the official press note claimed that "apadrinaron el enlace SS. AA. RR. don Francisco Javier de Borbon Parma y su augusta esposa".[98]

Family events were the only opportunities when at the time Mazón was being mentioned in the press, always in the societé columns. During the wedding of his daughter María in 1967[99] or during the engagement ceremony of another daughter Margarita in 1968[100] the only political heavyweight present was the former Carlist turned the Cortes speaker, Antonio Iturmendi. The 1971 wedding of a more distant relative was attended only by family and friends.[101] In the 1970s Mazón disappeared entirely from the public eye. Following death the only necrological note published in the press was this signed by his close family.[102]

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Mazon entry, [in:] Heraldica Familiar service, available here

- ^ he was married to Clara Gómez, Boletín Oficial de la Provincia de Santander 27.04.27, available here

- ^ La Rioja 24.08.16, available here

- ^ see 41 imgsExpte. nº 563 instruido contra MAZON SAINZ, Claudio por el delito/s de Desafección al Régimen., [in:] Pares service, available here, document #37, also El Avisador Numantino 07.02.12, available here

- ^ in 1897 he was mentioned as “conocido farmaceútico”, living in Haro, La Rioja 23.10.97, available here

- ^ in 1897 an unnamed brother died in early infancy, La Rioja 23.10.97, available here. Another brother, Ciríaco Mazón Sainz, died in 1899 at 22 months of age, La Rioja 26.08.99, available here.

- ^ ABC 15.05.91, available here

- ^ all children were Clotilde (1894), NN (1897), Ciríaco (1898), José María (1901), María Antonia (1906), Claudio (1911) and Maria de la Vega (1919), see files of Republican tribunals from 1937-1938, e.g. Expte. nº 559 instruido contra MAZON SAINZ, María Antonia por el delito/s de Desafección al Régimen, [in:] Pares service, available here

- ^ Heraldo Alaves 10.06.13, available here

- ^ in 1916 Mazón was noted in the press as visiting Vitoria; apparently he resided elsewhere at the time, La Rioja 24.08.16, available here

- ^ ABC 19.07.22, available here

- ^ Diario de Alicante 17.10.28, available here

- ^ she was Mazón's senior, Boletin Oficial de la Provincia de Logroño 03.06.22, available here

- ^ Anuario español y americano del gran mundo, Madrid 1956, p. 681

- ^ ABC 10.05.56, available here

- ^ ABC 11.06.89, available here

- ^ ABC 11.06.89, available here

- ^ her brother Antonio Sainz Palomera was a pharmacist from Cantabria, El Cantábrico 30.05.20, available here

- ^ in 1929 she married an entrepreneur of Mexican origin Justo López Arriola, La Voz de Cantabria 17.01.29, available here. Further fate of the couple is not known

- ^ she outlived Mazón by 8 years, and her death notice did not mention any children of her and Mazón, ABC 11.06.89, available here

- ^ D. Eugenio Mazón Verdejo, [in:] Centro Riojano de Madrid service, available here

- ^ Manuel Martorell Pérez, Carlos Hugo frente a Juan Carlos. La solución federal para España que Franco rechazó, Madrid 2014, ISBN 9788477682653, p. 152

- ^ Mazon Verdejo, Eugenio entry, [in:] official Cortes service, available here

- ^ Mazón Abogados website, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 03.02.36, available here

- ^ El Correo Español 31.12.08, available here

- ^ at least one José María's sister during her youth was also a Carlist and member of Comunion Tradicionalista; in Republican Madrid and at the age of 17 it cost her detention and incarceration; though no other charges were brought, in March 1937 a revolutionary tribunal sentenced her to loss of civil rights and one year in labor camp, see Expte. nº 205 instruido contra MAZON SAINZ, María Dolores (o MAZON SANZ) por el delito/s de Desafección al Régimen, [in:] Pares service, available here. Also in the spring of 1937 the younger brother Claudio, detained on July 19, 1936 and having spent 9 months in prison, was set free by another revolutionary tribunal, Expte. nº 563 instruido contra MAZON SAINZ, Claudio por el delito/s de Desafección al Régimen, [in:] Pares service, available here. Another sister, Maria Antonia, arrested in August 1936 and since then behind bars, in January 1938 was sentenced to 2 years in labor camp and loss of civil rights, Expte. nº 559 instruido contra MAZON SAINZ, María Antonia por el delito/s de Desafección al Régimen, [in:] Pares service, available here

- ^ “soy Carlista desde 26 de Febrero de 1901, lo que naci”, see Ilustre Colegio de Abogados de Madrid. Comisión Depuradora. Expediente personal del Letrado don José María Mazón Sainz, available here

- ^ La Rioja 23.12.23, available here

- ^ La Rioja 01.02.24, available here

- ^ José Luis Gómez Urdáñez, La Dictadura de Primo de Rivera y la República, [in:], Pagina Profesional de Luis Gómez Urdáñez 2017, p. 13, available here

- ^ Gómez Urdáñez 2017, p.14

- ^ Gómez Urdáñez 2017, pp. 14-15

- ^ Gómez Urdáñez 2017, pp. 14-15

- ^ Gómez Urdáñez 2017, p. 15

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 18.03.32, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 14.06.32, available here

- ^ El Cruzado Español 06.11.31, available here

- ^ Gómez Urdáñez 2017, p. 20

- ^ Gómez Urdáñez 2017, p. 31

- ^ Gómez Urdáñez 2017, p. 38

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 22.05.34, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 16.05.34, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 12.09.35, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 02.03.35, available here

- ^ Gómez Urdáñez 2017, p. 44

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 02.01.35, available here

- ^ Gómez Urdáñez 2017, p. 45

- ^ Pensamiento Alavés 20.04.36, available here

- ^ Mazón declared in the depuration questionnaire in 1940: “fui en colaboración con el ejército el organizador del alzamiento en la provincia de Logroño a [illegible] Carlista”, Ilustre Colegio de Abogados de Madrid. Comisión Depuradora. Expediente personal del Letrado don José María Mazón Sainz, available here

- ^ Roberto Pastor Cristóbal, Guerra civil, franquismo y democracia, [in:] Haro Histórico service 2017, p. 4, available here

- ^ during Christmas of 1936 he visited the Riojan requetes on their frontline positions in Sierra de Guadarrama; he was photographed in what looks like requete gear, see Agrupacion de Herreros de Tejada entry, [in:] Requetes service, available here

- ^ in some works his title is referred as president of "Junta Carlista de Guerra de La Rioja, María Cristina Rivero Noval, Política y sociedad en La Rioja durante el primer franquismo, 1936-1945, Logroño 2001, ISBN 9788495747013, p. 515

- ^ Aurora Villanueva Martínez, El carlismo navarro durante el primer franquismo, 1937-1951, Madrid 1998, ISBN 9788487863714, p. 30

- ^ apart from Mazón the delegation was composed of his younger brother Claudio Mazón Sainz, José María García Verde, Antonio Garzón and José Martínez Berasáin, Mercedes Peñalba Sotorrío, Entre la boina roja y la camisa azul, Estella 2013, ISBN 9788423533657, pp. 42, 126, Villanueva Martínez 1998, p. 30, Juan Carlos Peñas Bernaldo de Quirós, El Carlismo, la República y la Guerra Civil (1936-1937). De la conspiración a la unificación, Madrid 1996, ISBN 9788487863523, p. 259

- ^ Villanueva Martínez 1998, p. 31

- ^ Manuel Martorell Pérez, La continuidad ideológica del carlismo tras la Guerra Civil [PhD thesis in Historia Contemporanea, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia], Valencia 2009, p. 36

- ^ Peñas Bernaldo 1996, p. 262

- ^ Peñalba Sotorrío 2013, pp. 45, 127

- ^ however, Mazón did not form part of Rodezno’s entourage during the visit; the team consisted of Rodezno, Ulibarri, Florida, and Berasaín, Peñalba Sotorrío 2013, pp. 45, 128, Martin Blinkhorn, Carlism and Crisis in Spain 1931-1939, Cambridge 2008, ISBN 9780521207294, p. 288, Peñas Bernaldo 1996, p. 270

- ^ Peñalba Sotorrío 2013, p. 56

- ^ “más ferviente e incondicional adhesión. Rioja carlista, sin una sola excepción de sus militantes, se cuadra con el máximo respeto y con la mano en la boina, fría, serena y consciente le dice ¡A sus órdenes, mi general!” Peñas Bernaldo 1996, pp. 279-280

- ^ Diario de Burgos 23.04.37, available here

- ^ however, Mazón was not nominated the provincial Logroño FET jefe; this post went to another Riojan personality loosely associated with Carlism, José María Herreros de Tejada y Azcona

- ^ most historiographic works on the 1937 unification present Mazón as a secondary personality, whose elevation resulted from familiarity and loyalty to Rodezno, who hand-picked a second-rate local leader; in the 1970 work on unification Rodezno is mentioned 62 times, while Mazón is listed only twice, compare Maximiliano García Venero, Historia de la Unificacion, Madrid 1970. Similar perspective in Peñalba Sotorrío 2013 (19 vs 5) and Peñas Bernaldo de Quirós 1996 (54 vs 5)

- ^ Pensamiento Alavés 22.06.37, available here

- ^ Pensamiento Alavés 22.06.37, available here

- ^ Villanueva Martínez 1998, p. 51

- ^ Manuel Santa Cruz Alberto Ruiz Galarreta, Apuntes y documentos para la historia del tradicionalismo español, vols. 1-3, Sevilla 1979, p. 159. On the carefully structured appointment list, with nominees listed sequentially in what appeared to be the order of importance, Mazón was listed as the 9th Carlist (after Rodezno, Bilbao, Muñoz Aguilar, Baleztena (J), Urraca, Valiente, Fal and Oriol, ahead of Florida, Arellano, and Toledo. Overall he was listed at position 29, see Diario de Burgos 21.10.37, available here

- ^ he was not listed as member of Junta Politica in March 1938, Heraldo de Zamora 10.03.38, available here

- ^ Pensamiento Alavés 16.02.38, available here

- ^ Proa 08.03.38, available here

- ^ Pensamiento Alavés 20.06.38, available here

- ^ see e.g. analysis of conflicts between the Falangists and Carlists in Peñalba Sotorrío 2013

- ^ Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 188

- ^ Ana Marín Fidalgo, Manuel M. Burgueño, In memoriam. Manuel J. Fal Conde (1894-1975), Sevilla 1980, p. 45

- ^ Mazón Abogados website, available here

- ^ some sources claim April, Rivero Noval 2001, p. 536

- ^ El Día de Palencia 15.03.39, available here

- ^ Boletín del Movimiento de Falange Española Tradicionalista 10.09.39, available here

- ^ e.g. in 1940 he took part in honor guard at the tomb of José Antonio Primo de Rivera, ABC 21.11.40, available here

- ^ already in April 1940 Mazón was admitted to Colegio de Abogados de Madrid, Ilustre Colegio de Abogados de Madrid. Comisión Depuradora. Expediente personal del Letrado don José María Mazón Sainz, available here

- ^ Proa 19.08.41, available here

- ^ Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 188

- ^ Pensamiento Alavés 23.11.42, available here

- ^ see Ilustre Colegio de Abogados de Madrid. Comisión Depuradora. Expediente personal del Letrado don José María Mazón Sainz, available here

- ^ Mazón Abogados website, available here

- ^ Mazón Abogados website, available here

- ^ last information on Mazón's role in the Bank of Spain comes from 1963, Santiago Olives Canals, Stephen Taylor (eds.), Who's who in Spain, Madrid 1963, p. 988

- ^ see Nosotros section of the corporate Mazón Abogados website, available here

- ^ Anuario español y americano del gran mundo, Madrid 1968, p. 729

- ^ in November 1942 the Carlist jefe delegado Manuel Fal Conde issued a note which allowed re-entry into the Comunión to these which by virtue of mistake or misinformation had joined FET; the exception was made in case of Rodezno, José María Oriol, José Luis Oriol, Esteban Bilbao, Julio Muñoz Aguilar and Juan Granell Pascual; despite his earlier role Mazón was not blacklisted. Mercedes Peñalba Sotorrío, Entre la boina roja y la camisa azul, Estella 2013, ISBN 9788423533657, p. 143

- ^ Imperio 11.11.54, available here

- ^ Imperio 09.02.56, available here

- ^ Diario de Burgos 09.02.61, available here

- ^ Diario de Burgos 09.03.63, available here

- ^ Martorell Pérez 2014, p. 152

- ^ ABC 13.07.58, available here

- ^ ABC 04.02.68, available here

- ^ ABC 20.02.68, available here

- ^ ABC 08.01.71, available here

- ^ ABC 19.08.81, available here

Further reading

[edit]- Maximiliano García Venero, Historia de la Unificacion, Madrid 1970

- José Luis Gómez Urdáñez, La Segunda República, [in:] José Luis Gómez Urdáñez (ed.), Aldeanueva de Ebro histórica, Logroño 2015, ISBN 9788493911423, pp. 242–283

- Mercedes Peñalba Sotorrío, Entre la boina roja y la camisa azul, Estella 2013, ISBN 9788423533657

- Juan Carlos Peñas Bernaldo de Quirós, El Carlismo, la República y la Guerra Civil (1936–1937). De la conspiración a la unificación, Madrid 1996, ISBN 9788487863523

External links

[edit]- Carlists

- Members of the National Council of the FET-JONS

- People involved in road accidents or incidents

- Politicians from La Rioja

- Roman Catholic activists

- Spanish anti-communists

- Spanish civil servants

- 20th-century Spanish lawyers

- Spanish monarchists

- Spanish municipal councillors

- Spanish people of the Spanish Civil War

- Spanish people of the Spanish Civil War (National faction)

- Spanish Roman Catholics

- 1901 births

- 1981 deaths